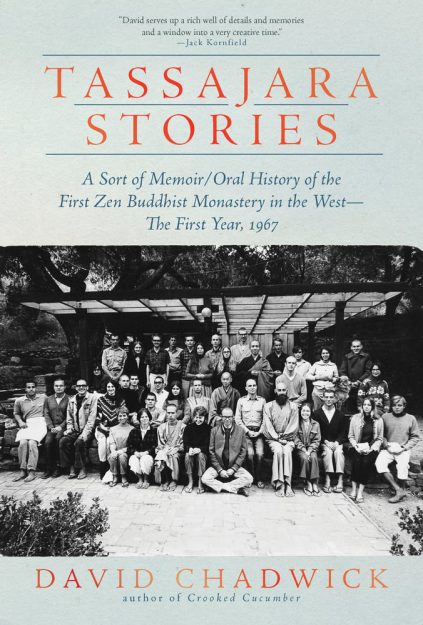

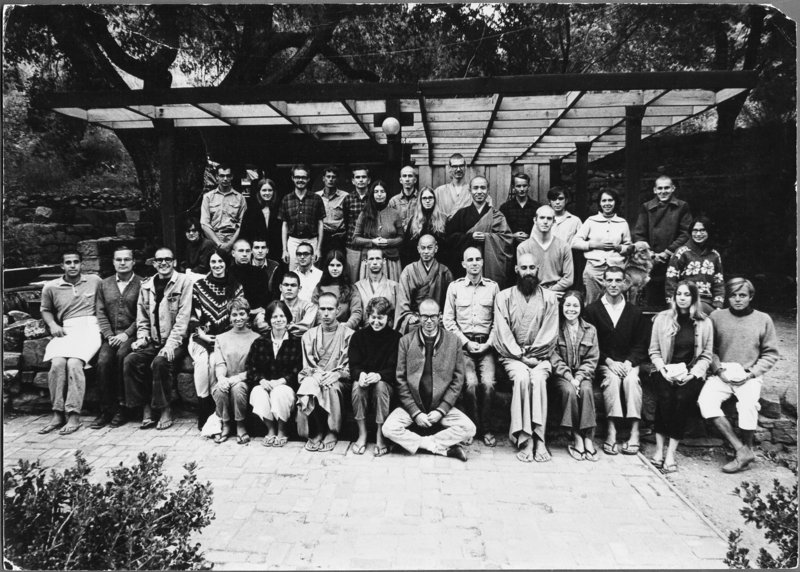

Tracing Beginnings at Tassajara

In an excerpt from his new memoir, author David Chadwick looks back at the opening of the first Zen center in the West. The post Tracing Beginnings at Tassajara appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Shunryu Suzuki was a man with many honorifics. Some of the oldest students referred to him as Reverend Suzuki. Others called him Suzuki Sensei. I heard a member of the Japanese American congregation call him Suzuki San. His wife called him Hojo San, which meant the abbot of a temple.

There was one more honorific that had been used some but which at that time became official—roshi. Alan Watts had written a letter saying Suzuki should be addressed that way, that it was the way Zen masters were addressed in Japan. Suzuki didn’t ask for it, but he acquiesced—after a hard laugh. So that’s what I called him—Suzuki Roshi or just Roshi.

Many people had trouble sitting in lotus, but I was one of the fortunate ones who didn’t. It did hurt toward the end of a period, but almost everyone else was still, so I was too.

When zazen was over, there was service, which started with us bowing to the floor nine times at the sound of the large deep bowl bell. Then we chanted the Heart Sutra three times. That was dynamic. At first, I was a little spooked by the bows to the floor, but soon I saw them as a fitting exercise after sitting cross-legged for so long.

We didn’t really sit for just forty minutes. That’s how much time there was between the bells that began and ended zazen. It was good to be seated at least a few minutes before the bell for the first period, and some people would be there ten or more minutes early. There was afternoon zazen at 5:30, followed by a briefer service, and Wednesday evening and Sunday morning lectures by Suzuki or [his assistant Dainin] Katagiri if Suzuki was away.

There was an extended schedule on Saturdays in which there were two zazen periods in the morning. We’d sit for forty minutes, then walk slowly for ten minutes. That was called kinhin. After the kinhin we’d sit for forty minutes again. Then there was service, a silent work period, and a silent meal.

We ate on trays, with chopsticks, while sitting on cushions, on tatami on the sides and goza mats in the middle. A Chinese American student named Bill Kwong was the cook for the Saturday breakfast, and it was almost always the same—white rice porridge, miso soup, some pickled cabbage or cucumber, a raw egg to mix with the hot rice. Sometimes a new student would think it was a hard-boiled egg and break it all over themselves. Tea poured into the empty rice bowl finished it off.

Before we were served, Bill would bring a little offering tray of food and step up to place it on the altar. Then he’d bring out Suzuki’s breakfast tray and offer it to him. Then he’d offer a tray to Katagiri.

Suzuki and Katagiri’s seats were on the elevated platform, where the altar and bells were. Bill had an impressive style. He would slowly exit the kitchen with a tray held with two hands just below eye level. Then he’d swivel his back to us and move sideways facing the altar. As he moved along, I would gaze at his toes, impressive long toes, toes that would creep sideways one by one, each stretching to its limit. His toes seemed to be independently propelling him sideways while his feet and the rest of his body passively followed along.

Everything we did was called a form of practice. Practice, I learned, was extending zazen into daily life. Zazen and kinhin were formal zazen practices. Chanting, bowing, lectures, work, meals, and walking home were all zazen in action. From what I gathered, everything was zazen—or at least potentially so.

In a lecture Suzuki said that Zen was nothing special, just sitting, sipping a cup of tea. Indeed, the practice at Sokoji was a testament to this. Just arriving, doing what we did there quietly, and departing. I’d nod to others. Maybe we’d have a few words. Smooth as satin. It filtered into my time away, and my life became more settled.

Not many rules—arrive clean and on time or sit in the balcony, don’t come high. No one asked me to join or hit me up for money. There was a donation box outside the zendo, though—and a sign on a bulletin board that read, “We need money to buy more kapok. See Pat.” I found Pat. She was older with white hair. I gave her five dollars for kapok. She bowed and said thank you. Then I asked what kapok was. She said it’s what we stuff the zafus with.

“Oh, I see. And what are zafus?”

“The round cushions we sit on.”

One benefit of practicing Zen was that it expanded my vocabulary.

The Site

Katagiri had a desk downstairs in an office that was for the business of the Japanese American congregation. He was friendly, so once, when I got to Sokoji too early for the 5:30 p.m. zazen and found him in his office, I went in and said hello. He said hello, too, and in a welcoming way. I asked him what the chart on the wall was about. He explained it, showing how much money had been raised toward the construction of a new temple on a lot around the corner that the Japanese congregation was purchasing. “What will happen to this building when they move to the new one?” I asked. “Maybe Zen Center will buy it,” he said. “But that would be many years from now.” The red in the thermometer had a long way yet to climb. “Little by little,” Katagiri said, smiling.

So I was coasting along enjoying this new scheduled and calm carefree lifestyle when one day people were talking in the hall instead of leaving. They said there was a place in the woods down south that Zen Center wanted to use as a retreat. The board had approved its purchase, and $2,500 had already been put down on it. The total price was a dizzying $150,000, with $25,000 due in mid-December.

Mid-December? That was two months away. People were excited. It was as if the building vibrated and echoed with the revving up of a dormant generator.

On September 14, the board authorized Richard Baker to negotiate and sign a contract. Silas Hoadley, the treasurer, would fill in the blanks and deal with the details. People trusted his judgment and felt he’d be a good check in case the optimism of the moment got the Zen Center into shaky financial territory.

Overnight, this group was squeezing every cent out of any talent and contact they had—we had. I started getting to know more people. Ardis Jackson and Trudy Dixon were sitting at a desk downstairs making handwritten notes requesting donations. The notes were sent in hand-addressed envelopes to people, many of whom were on Richard’s contact lists, which included his own, and those he got from Zen popularizer Alan Watts, beat poet Allen Ginsberg, and other friends of Zen Center.

The Japanese congregation now had to share their sleepy office with our supercharged activity. There were boxes of brochures stacked against the wall. I took one out and unfolded it. It announced in bold letters: A SITE FOR A ZEN MEDITATION CENTER IN THE CALIFORNIA MOUNTAINS. There were black-and-white photos of mountains, rocks, woods, meadows, a trickling streamlet.

Spending the afternoon on a cushion at the low table in his office, at the request of his student, artist Willard Mike Dixon, Suzuki concentrated on creating an enso, a sumi circle, for a poster announcing a benefit art show. Dipping his brush in the black ink, he drew one incomplete circular stroke after another, going through sheet after sheet of rice paper, until he brushed a stroke that satisfied him.

I asked him if he’d sign one of the rejects. An older student standing nearby kicked me gently and said in a soft voice, “That’s not done.” But Suzuki did it, and I took it back to my place to proudly tack on to the bare wall.

I had a little trust fund controlled by my mother. Not much. Not enough to live on. She agreed to a donation. I enjoyed the surprised look on Richard Baker’s face when scruffy me walked in and handed him a check for $500.

There was a big chalkboard in the hall showing how far we had to go. I could see that we’d already raised over $6,000. Suzuki looked at it, pointed to the $25,000 goal, and said, “If we can get this much, we can come up with it all.”

A Conversation

Once a month there was a one-day sesshin at Sokoji. Richard said sesshin meant mind-gathering. So I decided to gather my mind and attend it—with some apprehension. The usual period in the morning, and in the afternoon, seemed like plenty of zazen to me, and I went to extremes not to miss any. I’d run for blocks sometimes to get there to be still.

In the second morning period, it was challenging not to move my legs the last ten minutes. Now, there would be more sitting till 5 p.m., broken up by kinhin, services, breakfast, and a work period. For the lecture we also sat on our zafus. In the lecture, Suzuki said, “First your intellectual activity will calm down, and later, your emotional activity will follow.”

During the afternoon, Suzuki gave dokusan, private interviews, in the office downstairs. I sat outside with three others. I’d been told I should ask him a question. As I sat there, I was thinking about what to ask.

Suzuki had only recently come back from a trip to Japan. Silas had introduced us. We had seen each other after each service when we bowed together at the door to his office, as everyone did on their way out to get their sandals or shoes on. I felt like Suzuki was looking right into me every time we bowed, not as if he was sizing me up, more like he was saying hello to a vast part of me I wasn’t in touch with. But I didn’t know who he was except someone who seemed to be awfully accepting and accepted by those of us filing by to bow with him. Later, I saw him standing in his office talking to someone, and I realized he was awfully short. He hadn’t come across as that small when he bowed with me after service. It was like he wore a different size for different occasions.

Now, I had to ask him a question. I hadn’t read much about Zen. Before coming to Zen Center, I’d heard it was about whacks and yelling and fantastic insights, but there didn’t seem to be any of that going on. There was sitting on and scrubbing the floor. What we did was all stuff I could do. I’d heard him say in a lecture that this practice is enlightenment, not a means to attain it, so you don’t have to seek enlightenment—just do the practice. That was a relief to hear.

I’d heard him say in a lecture that this practice is enlightenment, not a means to attain it, so you don’t have to seek enlightenment—just do the practice.

Finally, it was just me sitting alone downstairs in the deserted dank hall, with the fading paint and dusty smell. I thought we’d have to have a lot more work periods to get this whole place spiffy.

“Excuse me.” I heard a soft voice and looked up. Suzuki was standing at the doorway, the brown sleeves of his robe dangling down to his hand, which held a short curved polished stick. He looks so harmless, I thought. Surely he doesn’t hit people with that. I sat there with my head turned looking at him.

“I rang the bell,” he said, “You should answer by ringing yours.”

“Bell? Oh!” I said and picked up the handbell next to me and hit it.

“Too loud,” he said, wincing. He took a few steps toward me, squatted, picked up the bell, and rang it. It had a ring that took me away for a second. “Like that,” he said. “Not too much.”

In the office, there were two square flat black cushions, zabutons, on a goza mat with zafus on them. On a small square table there was a little Buddha figure, a lit candle, and smoking incense.

Someone had shown me the forms for dokusan already, but he went over it again. Bow on the floor toward the altar three times, and then stand up and bow once on the floor to him. After that, I positioned myself on the zafu with my legs crossed in full lotus facing him while he folded his legs and adjusted his robes around them. We were quite close to each other—close enough for him to reach over and whack me with that stick. But I didn’t feel intimidated by him. He had a gentle manner.

I sat looking at him for a brief moment, and then he said, “You sit very well.”

Thanks, Granny, I thought, remembering my mother’s mother often telling me, “Sit up straight!”

“I like sitting like this,” I said. “I don’t know what it’s all about, but I like it.”

He seemed a soft brown pyramid. “You look like you were born sitting,” I said and looked him in the eye.

He averted his. “Do you have some question?”

Oh, oh. Too buddy-buddy, I thought. “Hmm. I don’t really have a question. I’m pretty new and just seeing what this is all about. I decided to sit for a year here. And then . . . I don’t know.” I was looking at his hands. They were stroking his stick. “Is that OK?”

“That is pretty good,” he said. “Better not to have too many questions.”

“I could ask a question for my mother,” I said.

He nodded.

“My mother believes in reincarnation. Do you believe in reincarnation?”

“Oh, your mother believes in reincarnation? That is very unusual.”

His voice was quiet yet firm. It reminded me of Mr. Gardener, a 90-year-old man at the tennis courts where I’d played as a kid. He’d tell us stories, and I’d get lost in the mesmerizing quality of his voice. As with Mr. Gardener, I wanted to hear Suzuki talk more.

“Actually, I believe in reincarnation too,” I said. “I have since she told me about it when I was still in elementary school. So do you believe in reincarnation?”

“I sometimes think so. But it is not something I know for sure. Maybe, maybe there is.” Good lord. He didn’t seem very sure of it for a Zen master.

“Where does your mother live?”

Ah, great, he wants to talk more. “In Texas.”

“Oh,” he said as if he were very impressed, “Texas. It’s very wide.”

“Not as big as Alaska,” I said, “but if you melt all the ice in Alaska, Texas will be bigger.” This is something I’d hear in Texas now and then after Alaska became a state and we were no longer the biggest.

“What does your mother think of your being here at Zen Center?”

“She likes it that I’m here. She says she figured I’d do something like this. But she wanted me to move out of the Fillmore closer to here, where it’s safer, and I did.”

“Yes, you should live close. And you should be near the older students. They can give you some guidance. Your life shouldn’t be all topsy-turvy,” he said, waving his stick back and forth in short arcs.

“Just keep sitting here and we will get to know each other. OK?”

“OK.”

He reached down, picked up his bell, and rang it. I got up, bowed to the floor toward him again, and walked out. I went back upstairs to more zazen, which entailed some leg pain and thinking about that dokusan. I didn’t get a cosmic hit like some people talked about, but still I liked it. I liked him. I envisioned Sokoji as a ship sailing on unpredictable seas, Suzuki as the trustworthy captain. And I had no interest in doing anything other than being onboard and going wherever that ship sailed.

♦

Excerpted from David Chadwick’s Tassajara Stories: A Sort of Memoir/Oral History of the First Zen Buddhist Monastery in the West―The First Year, 1967, publishing on September 23, 2025, Monkfish Book Publishing. Used by permission.

Troov

Troov