My Tongue Surgery

A Tibetan writer confronts a displaced self following years of Sinicization. The post My Tongue Surgery appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

A Tibetan writer confronts a displaced self following years of Sinicization.

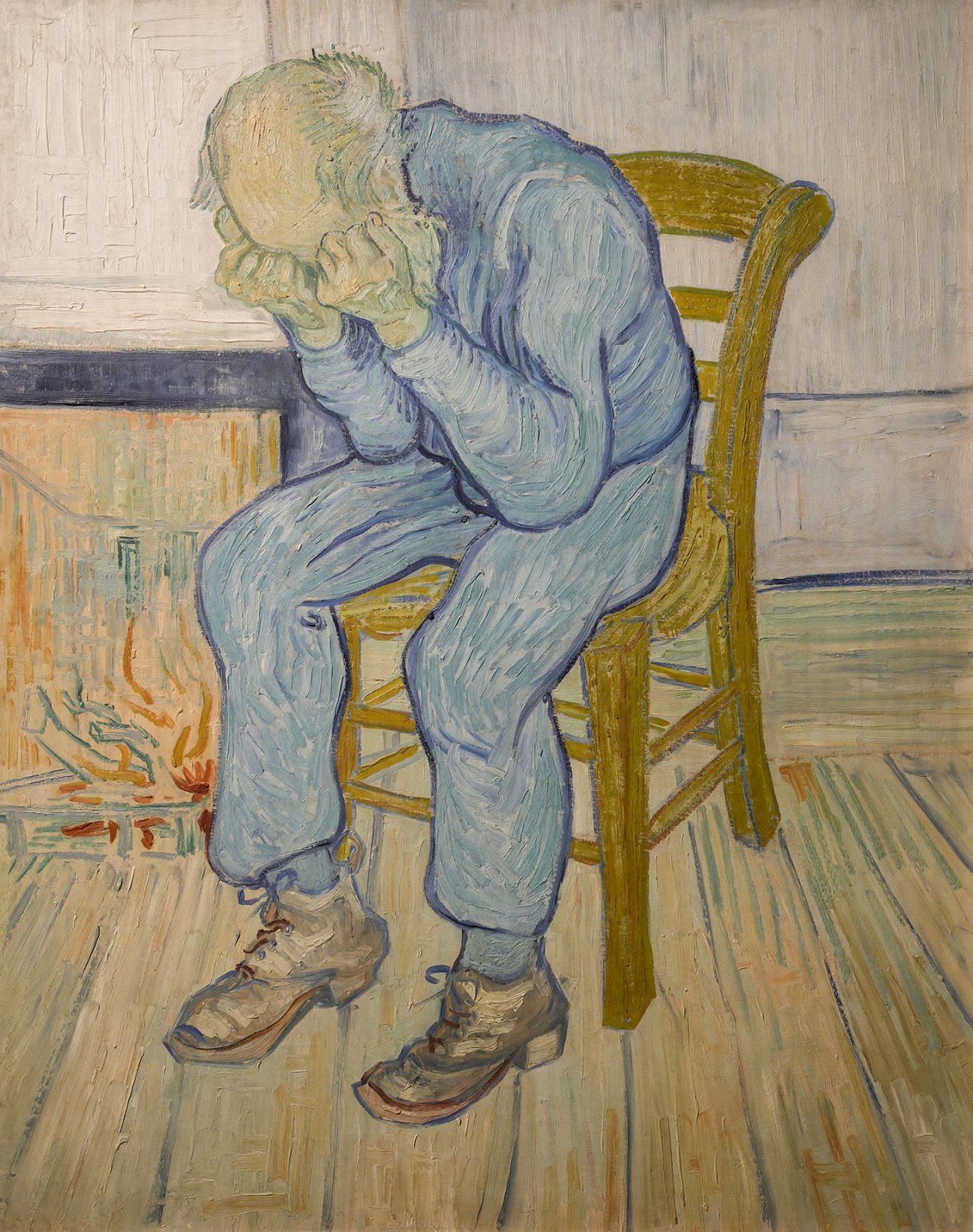

By Tsering Woeser, translated from the Chinese by Fiona Sze-Lorrain Dec 28, 2025 Photo courtesy Tsering Woeser

Photo courtesy Tsering Woeser

In the early spring of 1981, I graduated from junior high school in an increasingly sinicized town called Kangding in eastern Tibet (In Tibetan, Kangding is also called Dartsedo). As it happened, the Southwest University for Nationalities in Sichuan was recruiting Tibetan students for its foundational preparatory program. An equivalent to the Chinese high school program, this course of study was launched in 1985 and aimed to accelerate cultural assimilation. It proved to be a successful experiment in Tibetan classes and former secondary schools in numerous cities including Beijing and Shanghai. Of course, the unanimous official justification for such program was “to help Tibet groom talent.”

I enrolled in the program out of my own will, and certainly without coaxing from my parents. In the heat of my rebellion, I had no desire to let them restrain or control my life. Hardly aware of any difference between a Han Chinese place and a Tibetan district, I thought of Chengdu as a huge city full of thrilling novelties. Neither did I anticipate myself becoming gradually alienated from my own homeland and its culture.

Clad in his military uniform, Father sent me off to Chengdu. We took a long-distance bus ride, and on stiff seats rode over the towering Mount Erlang. (What is it called in Tibetan?) Past the mountain, the scenery outside was rich with greenery: crisp bamboos, large patches of vegetable lands, and branches lavished with fruits. Once we alighted, I was greeted with a pot before a street eatery, stuffed with lonely cooked rabbit heads that exuded an alluring smell. I was stunned and immediately thought of a Tibetan folk legend, how one turned harelipped when one consumed rabbit meat. Right before my eyes, a path meandering through mountains and valleys emerged, and a rabbit we call ribong in Tibetan suddenly vanished along the way.

Much of what awaited me was an exotic contrast to my old life in Kangding. Cuisine, clothes, accents. . . I started to indulge in braised eel in soy sauce, spicy rabbit heads, and frog legs. Aware of having violated taboos, I was made more aware of coming across as a superstitious “barbarian” had I not tried these dishes. Locals in Chengdu seemed to enjoy calling others “barbarians”: If you chickened out of eating rabbit heads, you were bound to be an idiotic barbarian. Chengdu is a humid basin. My Tibetan classmates and I were surprised when we woke up with our hair heavily curled. Most of the locals tended to stereotype such curls as a unique trait of ethnic minorities. So every morning we would violently comb our long, curly hair until it turned straight, and eventually trimmed it to ear length. Although our hair remained curly, it looked permed: We now each resembled a middle-aged woman in the streets of Chengdu.

Our foundational program was no more than a “tiny department” sealed off from the rest of the university. We took our lessons in two spacious classrooms in a corner of the campus and did not get to interact with the local students. In fact, we had no idea what they were learning, even though they shared our age. I imagined they must be following the same curriculum: After all, our textbooks were identical to theirs, nor did we have the chance to own a textbook in the Tibetan or Yi script. There were about seventy of us in all, with ages ranging from fourteen to sixteen. Most of us were Tibetan, some ethnic Yi. Only a smattering few spoke Tibetan or the Yi language. With time, all of us became fluent in the Chengdu dialect.

Relatives in Lhasa described my tongue as one “after surgery,” because when it came to traditional phonetics in Tibetan—trills, retroflex consonants, or alveolar consonants—I was as ignorant as any foreigner.

Nine years later, upon my return to Lhasa from Kangding, I realized the extent of changes that had occurred in me and how they took on a certain profound significance. Relatives in Lhasa described my tongue as one “after surgery,” because when it came to traditional phonetics in Tibetan—trills, retroflex consonants, or alveolar consonants—I was as ignorant as any foreigner. I could do no more than produce odd sounds, let alone say words aloud. I couldn’t even pronounce “Lhasa” properly in Tibetan.

My university experience was no less than an existential displacement. Over thirty minority nationalities, each with a distinct name, had enrolled in the entire Southwest University for Nationalities. While we seemed to live in harmony in a multiethnic setting, we failed to understand the history and culture of our various ethnic nationalities. We were taught the diverse ethnic festive meals, the songs and dances that tribes savored when drinking around the bonfire, and that was it. Once in a while, we would splash water over one another as a way of celebrating the Dai people’s Songkran festival. Although the “highlights” of a multicultural milieu instilled in me an acute awareness of my “Tibetan” plight at all times, none of us had ever received an authentic ethnic education.

I was capable of writing long eloquent speeches about Emperor Qin, who built the Great Wall of China, yet I knew nothing of the Potala Palace and its construction. I could memorize Tang poems and Song verses from back to front, but understood none of the poetry by the Sixth Dalai Lama Tsangyang Gyatso. I knew the stories of revolutionary martyrs in Red China inside out, yet had no inkling of our own heroes from the 1959 Lhasa uprising . . . Fortunately, I did not forget Lhasa, my birthplace. Since moving with my parents to eastern Tibet at the age of four, I carried with me a profound nostalgia and homesickness. It was only in the spring of 1990, a year after my college graduation, that I finally found the chance to return to Lhasa, serving as an editor for the state-run literary journal Tibetan Literature.

What I saw and experienced upon arriving in Lhasa astonished me. Childhood memories now a blur, I could only grapple with vague impressions of Lhasa from my father’s vintage photographs: How marvelous and timeless the capital city was. But the reality was nothing close to its history: Armed soldiers flooded the city, and military armored cars rumbled on while they ran over boulevards. In March 1989, many Tibetans including monks, nuns, and civilians took to the streets to protest against the Chinese government’s oppression of Tibetans in 1959. In retaliation, Beijing declared martial law in Lhasa for a year and seven months.

As I stood on the soil of Lhasa, a deep solitude swelled within me. No doubt this had something to do with my tongue surgery. I could hardly speak a complete sentence in Tibetan. Whatever I blurted out was none other than the standardized Mandarin with a Sichuan accent. My mother tongue is not Chinese: It had been displaced during my adolescence. I even wondered if my appearance had also changed drastically, since I had greedily eaten spicy rabbit heads and violated various taboos.

Another twenty years passed before I returned to Lhasa as someone who had lost herself. My self-pursuit, resistance, and the ensuing acceptance . . . ultimately to narrate stories of Tibet from my perspective today, took too long. In the end, no one can deny that these words I write are also written in the Chinese language. This is a fact that will forever sadden me. But all things in the universe exist for a reason: There must be a reason why I was and have been a displaced self. As the Tibetan saying goes, It is but pre-destiny when a bird falls on a rock. Thank goodness my heart wasn’t replaced.

I will never forget my first visit to Jokhang Temple. It signifies a vital turning point in my life, and like a powerful electric current, it steadily impacted my “dissimilated” self. It was dusk. My relatives, still preserving their Tibetan customs, brought me to the temple. For no reason, tears streamed from my eyes once I entered the sacred site. When I set eyes on the statue of the smiling Buddha, I couldn’t help but wail with grief. An inner voice spoke out to me, You’re home at last, before it was overwhelmed by a pang of pain: A monk nearby was sighing in Tibetan, How pitiful this gyamo* is.

2007, Lhasa

Revised—March 2014, Beijing

*Author’s note: In Tibetan, a gyamo refers to a Han Chinese girl.

◆

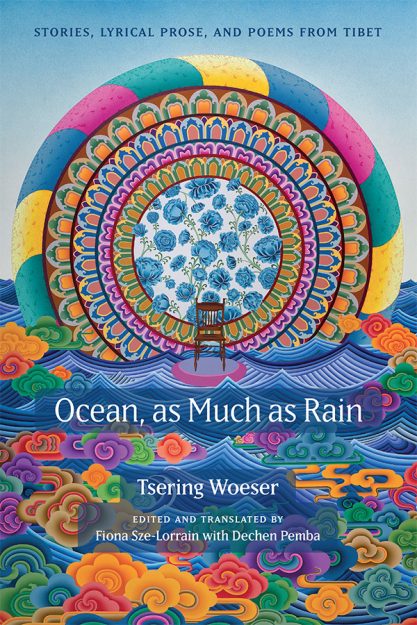

Excerpted from Ocean, as Much as Rain: Stories, Lyrical Prose, and Poems from Tibet by Tsering Woeser, edited and translated by Fiona Sze-Lorrain with Dechen Pemba. Copyright Duke University Press, 2026.

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

This article is only for Subscribers!

Subscribe now to read this article and get immediate access to everything else.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

MikeTyes

MikeTyes