Using Disappointment

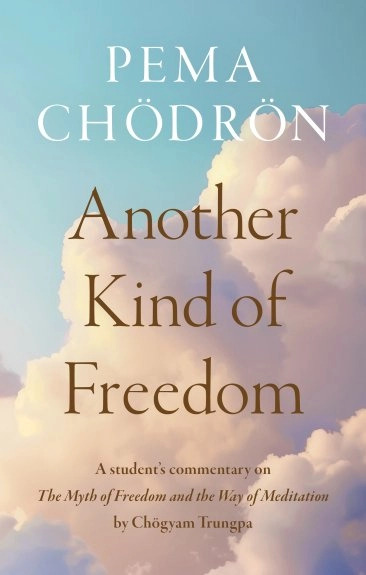

In her commentary to Chögyam Trungpa’s The Myth of Freedom and the Way of Meditation, Pema Chödrön describes dashed expectations as ego’s antidote. The post Using Disappointment appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

In her commentary to Chögyam Trungpa’s The Myth of Freedom and the Way of Meditation, Pema Chödrön describes dashed expectations as ego’s antidote.

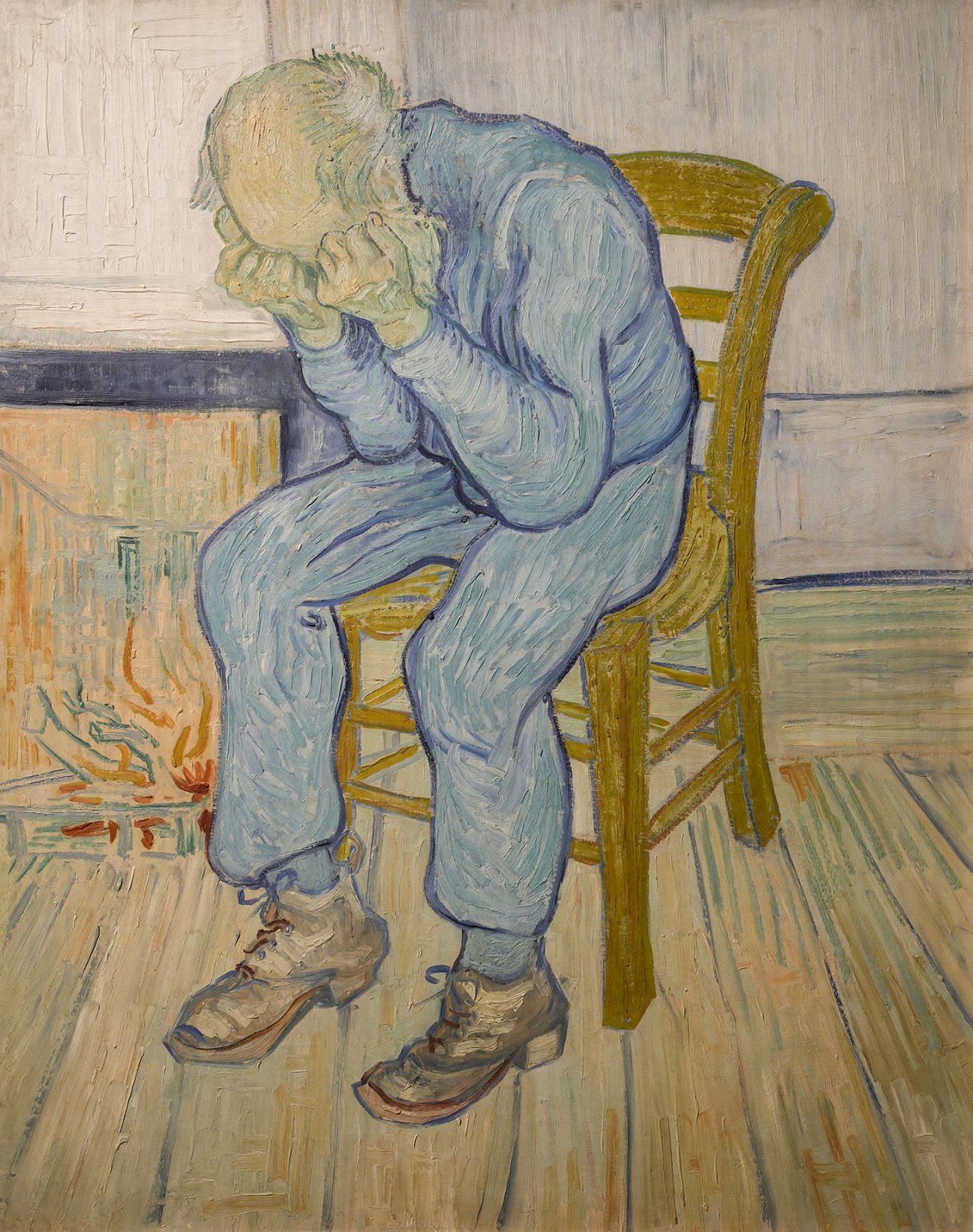

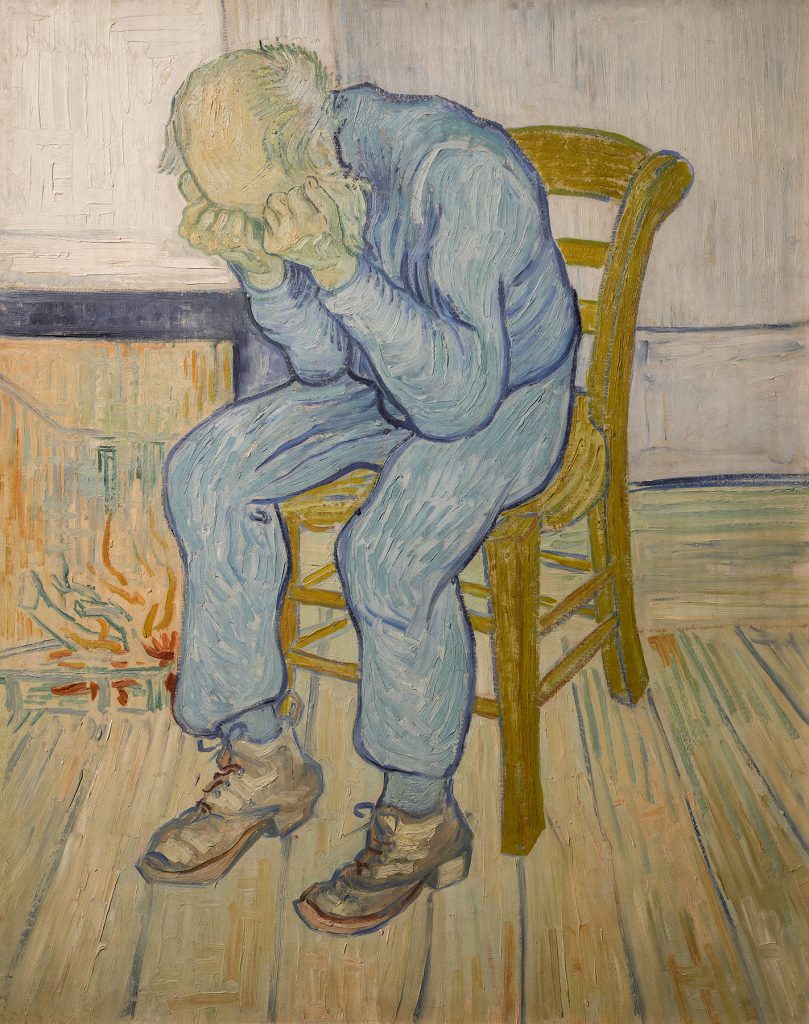

By Pema Chödrön Dec 30, 2025 Sorrowing Old Man (At Eternity's Gate), Vincent van Gogh, 1890, oil on canvas, 80 cm × 64 cm, Kröller-Müller Museum. | Image via Wikimedia Commons

Sorrowing Old Man (At Eternity's Gate), Vincent van Gogh, 1890, oil on canvas, 80 cm × 64 cm, Kröller-Müller Museum. | Image via Wikimedia Commons

In The Myth of Freedom and the Way of Meditation, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche repeats the theme of not using the spiritual path as a credential. As long as one’s approach to spirituality is based upon enriching ego, he says, then it is spiritual materialism. Instead of using drugs, alcohol, sex, shopping, or anything else, you use spirituality to avoid pain—the pain of your living situation or the pain of being who you are. This is the essence of spiritual materialism. As Oprah Winfrey once said, “If you’re seeking continual pleasure and always trying to avoid pain, you’re on the wrong planet.”

Rinpoche didn’t want people wasting their time trying to achieve a life with no ups and downs. He wanted Buddhism to be like good medicine for the people in our culture. So he took things that normally are thought of as bad news—for example, disappointment and boredom—and showed how they could be a big help on one’s spiritual path.

Rinpoche connects disappointment with expectation or wishful thinking: We expect the teachings to solve all our problems; we expect to be provided with magical means to deal with our depressions, our aggressions, our sexual hangups. But to our surprise we begin to realize that this is not going to happen. It is very disappointing to realize that we must work on ourselves and our suffering rather than depend upon a savior or the magical power of yogic techniques. It is disappointing to realize that we have to give up our expectations rather than build on the basis of our preconceptions.

When you’re disappointed, it is usually because things didn’t go the way you expected or the way you thought they were supposed to. As long as you have the expectation that you can get things to work out your way, you’ll be disappointed. Sometimes they do, sometimes they don’t; that’s the reality. A better approach is to do things wholeheartedly but leave the future open-ended. You know what you want, but you’re realistic. Outcomes are unpredictable.

Disappointment, however, can also lead to an aha moment: “Why am I so upset? I was holding on to some expectation of things going a certain way. That’s why I’m so upset.” You begin to see disappointment differently, as something that could help you wake up. Rinpoche appreciated disappointment because, as he says, it is without the ambition of the ego. The pain of disappointment pops the bubble of ego very effectively. Instead of building up your ego, it makes you feel more vulnerable. This of course is just what many of us don’t want. When we feel even the hint of vulnerability, we armor ourselves. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

The pain of disappointment pops the bubble of ego very effectively.

My experience with disappointment is that when you’re really let down and hurting, the teachings don’t change your emotional reaction. Whether it’s a small thing, like the restaurant being closed, or a major thing, like being betrayed in a relationship, the teachings don’t prevent you from having that disappointed feeling. This is an important point. Your emotional reaction may not change, but your response to that reaction changes. In my life, I don’t try to make everything okay. That would be my knee-jerk response. Instead I try to move closer to the feeling of disappointment and let it pierce me to the heart.

Recently something happened where I totally lost it and exploded in anger. This was quite unexpected and painful— after all these years of practice. What do I do with my embarrassment and the pain of having hurt somebody? I blew it; I made myself suffer, and I made someone else suffer. How can I stay present with those feelings so that I don’t create further pain by trying to get away from what just happened? These are the kinds of questions I ask myself. The disappointment doesn’t change; what changes is how I respond. I can get swept up in the emotional turmoil, or I can interrupt the momentum and not escalate. As Rinpoche would say, “We’re given choices every moment of our life to wake up further or go further to sleep.” Do I make matters worse, or do I taste the rawness of what I’m feeling and lean in?

As the ambition of ego dwindles, Rinpoche says we become like a “grain of sand”: We fall down and down and down, until we touch the ground, until we relate with the basic sanity of earth. We become the lowest of the low, the smallest of the small, a grain of sand, perfectly simple, no expectations. When we are grounded, there is no room for dreaming or frivolous impulse, so our practice at last becomes workable.

Becoming a grain of sand has nothing to do with being pitiful or self-denigrating. It’s the experience of getting out of your own way and becoming more receptive to the world: If you are a grain of sand, the rest of the universe, all the space, all the room is yours, because you obstruct nothing, overcrowd nothing, possess nothing. There is tremendous openness.

This is the opposite of the big-deal attitude Rinpoche describes so humorously in “Buddhadharma without Credentials”:

If I practice more, will I get credentials, so that I will be entitled to put “Buddha” at the end of my name? Maybe I could at least have “Arhat” or “Bodhisattva” at the end of my name: Jack Parsons, the Bodhisattva; Daniel Smith, the Arhat. The obvious answer to such notions is that the spiritual path is not divided in terms of grades.

Previously, I described a conversation where you’re connecting with someone and then you suddenly retreat into yourself. You split off, and “me” becomes more important than the other person. When you catch yourself doing that, try becoming a grain of sand. That is to say, stop talking to yourself and open further to the other person. Instead of shaming yourself or making it a big deal, you simply open to the other person. You get out of the way and listen. You allow for curiosity and appreciation.

◆

Adapted from Another Kind of Freedom © 2026 by Pema Chödrön. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO. www.shambhala.com

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

This article is only for Subscribers!

Subscribe now to read this article and get immediate access to everything else.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Koichiko

Koichiko